« Objets inanimés, avez-vous donc une âme ? » écrivait Alphonse de Lamartine. Dans une interrogation un peu similaire, le photographe Romain Baro s’est penché sur un objet à la fois simple et investi d’un pouvoir d’incarnation unique au sein du rite chrétien : l’hostie. En consacrant ces petits disques de pain azyme, le prêtre les fait passer, selon les mots de l’artiste, de « presque rien » à « presque tout », soit une parcelle du « corps du Christ », selon la formule consacrée, partagée avec les fidèles au moment de l’Eucharistie. Non croyant, Romain Baro s’est documenté sur la fabrication des hosties pour approcher ce mécanisme et comprendre la manière dont l’univers religieux s’inscrit dans le monde contemporain.

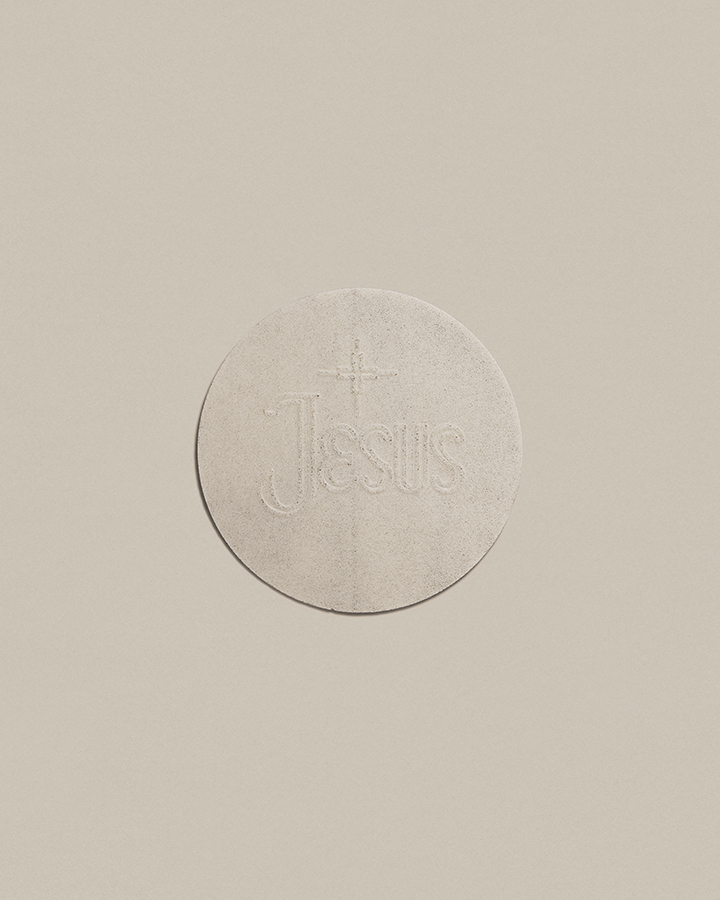

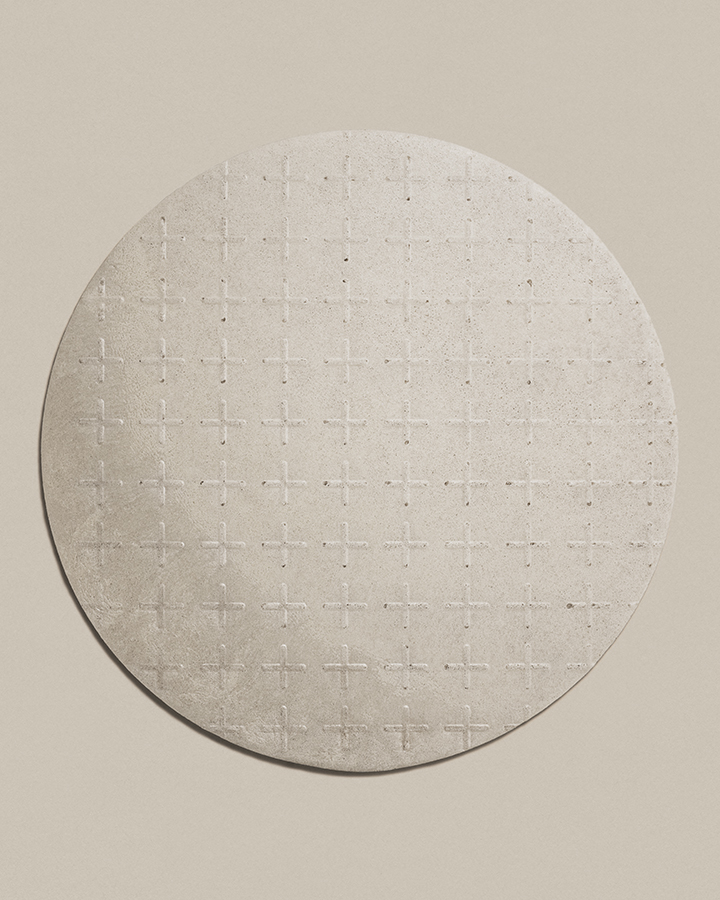

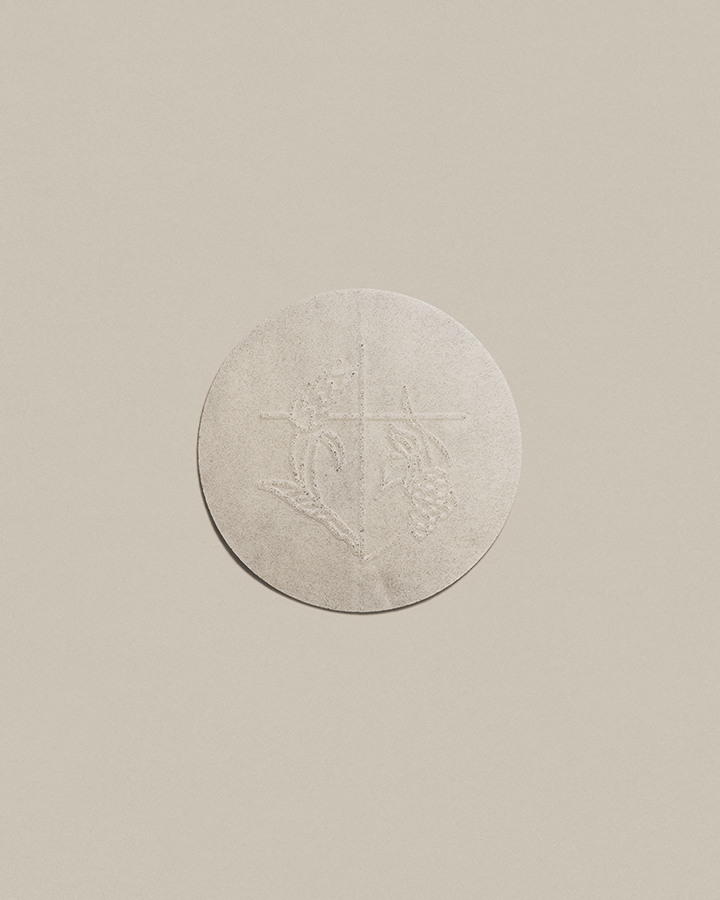

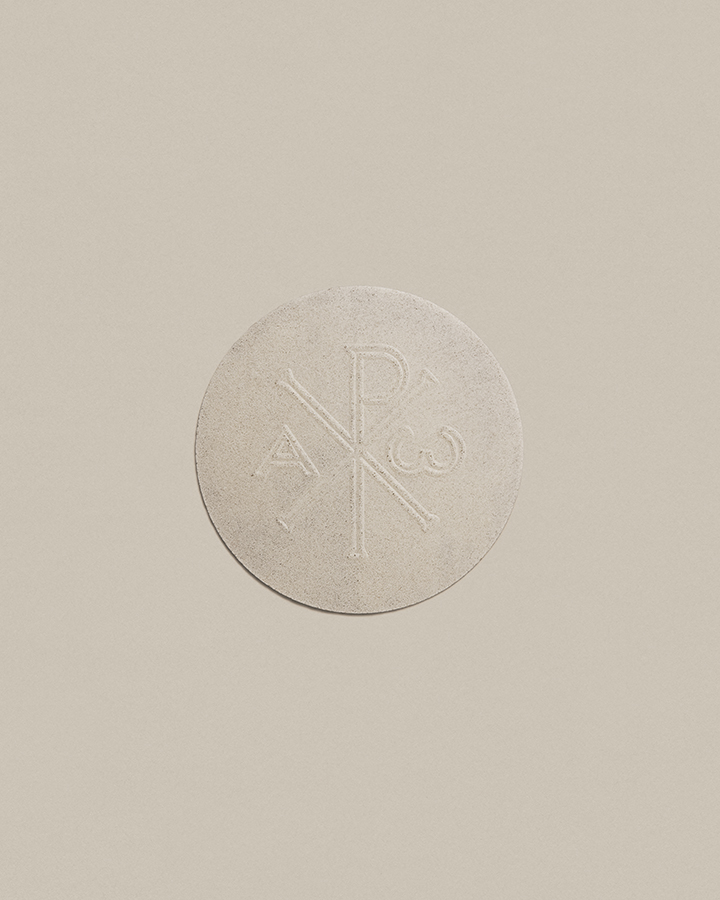

En latin, le terme hostia désigne la victime sacrifiée. Les hosties qui sont distribuées lors des messes sont des victimes symboliques, rappelant aux croyants le geste de Jésus lors de la Cène. Le plus souvent elles sont lisses, mais certaines sont parées de fines inscriptions en relief, lorsqu’elles ont un diamètre plus important ou sont produites à l’occasion de célébrations spéciales. On y décline alors tout un vocabulaire de formes et de signes, pouvant aller de motifs minimalistes à des figures richement détaillées.

Comme celle de tout artefact artisanal, la fabrication des hosties a évolué au fil des siècles. D’abord produites grâce à des fers à hosties, sortes de grandes pinces dans lesquelles était versée la pâte, elles sont aujourd’hui fabriquées par des machines automatisées. En France, une trentaine de communautés religieuses féminines, comme les Carmélites ou les Clarisses, en perpétuent la conception. Mais cette économie, comme bien d’autres à l’échelle locale, est mise en péril par la mondialisation : aujourd’hui, moules et hosties se trouvent facilement sur Internet et s’achètent comme n’importe quel objet de consommation. L’hostie est devenue un produit comme un autre, soumis aux lois du marché. En Europe, celui-ci est dominé par la Pologne et l’Italie.

Né en 1988, diplômé des Beaux-Arts de Nantes en 2011, Romain Baro s’intéresse aux systèmes (sociaux, politiques ou culturels) dans lesquels l’Humain évolue, aux manières dont il façonne son environnement, notamment à travers les objets. Pour son projet You have to blow, tissé autour de la présence de migrants sur l’île grecque de Lesbos, le photographe s’était attardé sur quatre objets dans lesquels sont investis des émotions, un passé ou un futur. Une manière également de s’interroger sur le statut de la photographie documentaire et son pouvoir de clarification du monde.

Pour la série présentée ici, l’artiste s’est procuré des hosties, dont il présente différents exemplaires avec la volonté d’en montrer la diversité. Portées par un fond neutre qui en révèle la surface et les aspérités, les pièces choisies relèvent de différents registres, qu’il s’agisse d’illustrations bibliques, de travaux typographiques ou de motifs simples déclinés de la croix ; certains s’apparentent à des motifs profanes. En soulignant la richesse du genre, le photographe met également l’accent sur une profusion propre au monde actuel, où la fabrication à la demande a remplacé l’offre limitée de la fabrication manuelle traditionnelle.

Derrière cet écart entre le mode de production des hosties et leur finalité se cache aussi un phénomène social : en France, on constate depuis une quarantaine d’années un net déclin du catholicisme et de sa pratique. « En moins d’un siècle, le nombre de personnes qui se déclarent des athées convaincus a presque doublé, constate Romain Baro. Cette évolution de la société reconfigure l’intérêt et l’adhésion des foules aux fictions religieuses, et nous interroge sur la capacité du catholicisme, et plus généralement des religions, à répondre aux grandes questions de la vie. »

Variations sur l’hostie, Pascaline Vallée

2020

Alphonse de Lamartine wrote: “Inanimate objects, do you have a soul?” In a somewhat similar question, the photographer Romain Baro looked at an object that is both simple and invested with a unique power of incarnation within the Christian rite: the host. By consecrating these small discs of unleavened bread, the priest takes them, in the artist’s words, from “almost nothing” to “almost everything”, that is to say, a piece of the “body of Christ”, according to the consecrated formula, shared with the faithful at the moment of the Eucharist. As a non-believer, Romain Baro has documented the making of hosts in order to approach this mechanism and understand how the religious universe fits into the contemporary world.

In Latin, the term hostia designates the sacrificed victim. The hosts that are distributed during masses are symbolic victims, reminding believers of Jesus’ gesture at the Last Supper. Most often they are smooth, but some are adorned with fine inscriptions in relief, when they are larger in diameter or are produced for special celebrations. In these cases, a whole vocabulary of forms and signs is used, ranging from minimalist motifs to richly detailed figures.

As with any craft artifact, the manufacture of hosts has evolved over the centuries. First produced with wafer irons, a kind of large pliers into which the dough was poured, they are now made by automated machines. In France, about thirty women’s religious communities, such as the Carmelites or the Poor Clares, perpetuate the conception of these wafers. But this economy, like many others on a local scale, is threatened by globalization: today, molds and wafers are easily found on the Internet and can be bought like any other consumer item. The wafer has become a product like any other, subject to the laws of the market. In Europe, the market is dominated by Poland and Italy.

Born in 1988, Romain Baro graduated from the Nantes School of Arts in 2011. He is interested in the systems (social, political or cultural) in which humans evolve, in the ways in which they shape their environment, particularly through objects. For his project You have to blow, woven around the presence of migrants on the Greek island of Lesbos, the photographer focused on four objects in which emotions, a past or a future are invested. This is also a way of questioning the status of documentary photography and its power to clarify the world.

For the series presented here, the artist has acquired hosts, of which he presents different copies with the desire to show their diversity. Carried by a neutral background that reveals their surface and roughness, the chosen pieces belong to different registers, whether they are biblical illustrations, typographical works or simple motifs of the cross; some of them are similar to secular motifs. In highlighting the richness of the genre, the photographer also emphasizes a profusion peculiar to today’s world, where made-to-order manufacturing has replaced the limited supply of traditional handcrafting.

Behind this discrepancy between the mode of production of the hosts and their purpose is also a social phenomenon: in France, there has been a clear decline in Catholicism and its practice for the past forty years. “In less than a century, the number of people who declare themselves convinced atheists has almost doubled, notes Romain Baro. This evolution of society reconfigures the interest and the adhesion of the crowds to religious fictions, and questions us on the capacity of Catholicism, and more generally of religions, to answer the great questions of life.”

Variations on the host, Pascaline Vallée